P.D. James emasculates a planet in Children of Men; Cormac McCarthy seeks salvation on The Road. By Kevin Rush

Released in 2006, but set in 2027, Alfonso Cuarón’s dystopian thriller, Children of Men is frenetic and at times intense, though ultimately incoherent and unfocused. In a near future where all women have become infertile, a disenchanted bureaucrat or journalist—it’s not clear—falls in with a band of violent extremists who needs his help to smuggle out of the country the first woman to become pregnant in a quarter century.

I saw this film when it first came out and didn’t much care for it. Cuarón was too busy weaving in themes of the Iraq War to focus on the central premise of the film: How would the world react to a global crisis of infertility? The fact that the human race is headed for extinction is incidental to Cuarón’s film, because, following 21st century trends of globalist adventurism, illegal immigration and terrorist reprisals, we’re going to kill each other anyway. Cuarón was also so seduced by the potential of emerging film technology to drop an audience into the middle of a video game, that he didn’t bother to immerse us in a story. Owen’s central character is mostly a hostage or bystander, dodging whiz-bang effects and only once rising to—not quite heroic, but stealthy—action.

The 1993 novel by British writer P.D. James is much more cerebral and clearly plotted than the film. Set in 2021, (how’s that for dystopian?) the premise remains the same, but the story is focused on the effects of the central phenomenon: infertility. The problem is not that women are barren, but that men cannot produce viable sperm. James’ dystopian future is a world of emasculated men, of which her Theo is emblematic. Though his name means ‘God,’ he is thoroughly impotent. Mourning the tragic loss of a child (an intense event rendered mundane in the film) and a subsequent divorce, Theo occupies a position as a university academic. And as if academics weren’t inconsequential enough, Theo hasn’t any students to teach. Although he’s mostly isolated within his shrinking community, the men around him are similarly useless.

James’ narrative does not match the film’s break-neck pace, as she paints her world in meticulous detail. Yet, that world is capable of erupting in sudden, senseless and brutal violence, even among those who are ostensibly trying to save it. In this way, James’ novel is a study on the consequences of eroding masculinity. Not peace and harmony as the “new man” advocates of the 70s promised, but downward spiraling disorder. This is a lesson for our age, where traditional masculine virtues are disdained, enabling the rise of venal, vain and scheming individuals, who have brought us to our current state of kakistocracy and civil unrest.

Ms. James does not provide an epigram indicating the source of her title. IMDB cites Psalm 90, which reads in pertinent part:

“Thou [God] turnest man to destruction; and sayest, Return, ye children of men.”

James is more than hinting that our straying from the natural order has led us to ruin.

In my search for a possible source of the title, I came across this quotation attributed to Helen Keller, which I also found apropos:

“Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.”

Seeking illusory safety emasculates men who must strive, even at great risk, to remain vital. A society cheering the bravery of boys who steal track medals from girls needs to be reminded of the necessity of authentic masculinity. Children of Men jogs that memory, and for this I give it a mild nod. It’s thoughtful and creative, though in the final analysis, I think the awesome concept deserves both a better book and a better film.

Similar to Children of Men, The Road begins after an unexplained catastrophe has permanently altered the world. In The Road, we assume a nuclear war scorched the Earth, killing all plant and, eventually, animal life. All that’s left are a handful of human survivors, running short on food and time. In this setting, a terminally ill father takes his young son on a trek down a road towards the sea.

Released in 2009, The Road went nowhere. Despite a strong cast, which included Viggo Mortensen, Charlize Theron, Robert Duvall and Guy Pearce, and bolstered by newcomer Kodi Smit-McPhee, the film suffered from B-movie scripting and pedestrian direction. The script relies on voiceover exposition that reveals the horrors to come, robbing us of the surprises that were so devastating in the book. John Hillcoat, an Australian director mostly known for pop music videos, just doesn’t seem to have been up to the subject matter. I’d say he was painting by numbers, but like a child’s watercolor, all tones merged into a dull grey. His defenders might say that’s the world he was required to depict. Fair enough. Yet Cormac McCarthy depicts that world vibrantly and urgently in his novel, and Hillcoat was not able to transfer those emotions to film.

So, here’s where I confess I read the book before I saw the film. And I’m glad I did. Because, while the movie is not bad, the book is a masterpiece of American literature. Not that I thought it would be. When the book first came out, I passed on it, wondering why someone of McCarthy’s immense talent would care to revisit a tired scenario of the 1950s and 60s. But The Road is not a retread of On the Beach or Cat’s Cradle. It is a unique tale of a father’s love for his son, and his determination to protect him from rampant evil, preserve his innocence, and provide him a dignified life even among the ashes of civilization.

McCarthy’s book, which has been hailed as a great Catholic novel, brilliantly depicts the salvific purpose of remaining virtuous in a realm where evil is more seemingly advantageous. And unlike Hillcoat’s frontloaded film, McCarthy lets no detail of his world drop until the precise moment when it will have its most devastating emotional effect. The Road is a great story greatly told. These days, many people joke about hoping for the sweet meteor of death to snuff out what’s become of our world. The Road teaches us to be careful what we wish for, but also to make the most of it.

Disclaimer: Links in this column may be affiliate links. When you click on an affiliate link and make a purchase, the website receives a small commission, at no additional cost to you. These commissions help support future writing, like the book you see below.

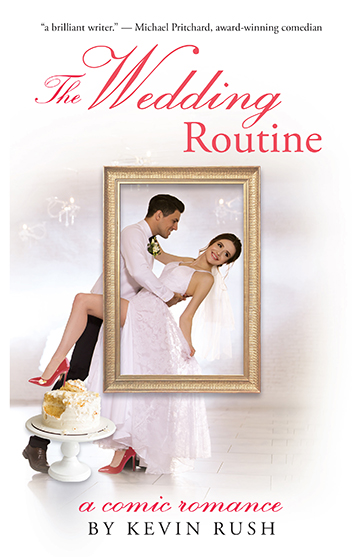

You can freely support the success of my new book, The Wedding Routine, by entering our Goodreads Giveaway now!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Wedding Routine

by Kevin Rush

Giveaway ends December 20, 2021.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Recent Comments