by Kevin Rush

As Ian Sheehy crept down the rain-washed alley, scratchy music played from a kitchen radio. Dinah Shore—or was it Jo Stafford?—sang For Sentimental Reasons. In the black of the narrow passage, light from apartment windows shone in white circles in the puddles he stepped over and around, almost like votive candles. He reached a spot below the fire escape and gently pulled the ladder down. The metal structure ached and rattled up to the roof, and gonged like a church bell. The pressure that had been building all day in his temples and behind his eyes thundered briefly, then eased as the echo died away. Ian expected the noise to draw dark silhouettes to the lighted windows, but none appeared.

Carmella’s bedroom window was dark. In the kitchen, the lower curtains were drawn, but the shade was up, and soft light leaked out of the living room, turning the cream-colored walls orange like a Mediterranean sunset. He climbed, careful not to shake the ladder. His head couldn’t take the rattling right now, and he didn’t want Carmella’s family to discover him. He only wanted to talk to her, quietly, alone, at her bedroom window, not cause a scandal, sneaking around like a thief.

He’d thought of telephoning. But she might have told him, “Not tonight. Wait ‘til tomorrow or Thursday.” He knew he couldn’t wait, and he’d press her ‘til she said, “Okay, come.” But would she wait for him? Or would she deliberately leave the apartment, go out with some other guy, any guy, so she wouldn’t be home when he got there? Snippy as she’d been, she might do that to embarrass him. And to escape the prying eyes of her family. Ian could understand that; he had prying eyes at home, too.

He wanted to go back to when they’d met. That corny church social to welcome home the GIs. Already back six weeks, Ian had got his uniform pressed and finally put on the ribbons. Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary was an Italian parish in South Brooklyn, a trek from his Irish-German enclave in Bushwick. But the dance would have Italian food, and most importantly, Italian girls.

Ian wondered then if they rinsed their hair with rosemary water or lavender. Did their skin glow from olive oil and chamomile? Were their teeth straight and white as ivory? He’d practically broken into a sweat as he entered the auditorium. For a lightly freckled, rusty blonde, this was uncharted, if not hostile, territory. He offered to pay at the door, but a full-figured older woman told him, “Gratis per i nostri eroi!” The band was just settling in, so Ian lined up for a plate of chow. The garlic and tomato fumes made his head swim and his gut ache. He chose the stuffed shells with a side of sliced sausage and peppers, then looked for a seat in the corner of the room. He wanted to eat and observe, unobserved.

It was from that corner, his mouth full of ricotta, that Ian had spotted Carmella, dressed like an Andrews Sister. Broad, padded shoulders tapered in a sharp V to a narrow waist, then a wondrous pair of hips curved deliciously outward and down the sweetest set of gams this side of Betty Grable. She wore a pillbox hat jauntily off-center, on a dark, curly mane that framed a perfect heart-shaped face. Warm opal eyes were separated by a classically sharp, yet delicate, aquiline nose. A man could search every town from Sicily to Tuscany and never find a more perfect specimen of bellezza femminile.

Ian stepped off the fire escape ladder to the landing and crouched low. Shadows on the curtains told him someone was in Carmella’s kitchen. He could hear a woman’s voice: Mrs. Battaglia.

“Why you stay home, Carma? With you sad face? You Irish boy, he no come ‘round?”

Now he’d hear it. Truth from her own lips. But Carmella’s voice was muffled. Sob choked, maybe. A shadow thrown on the wall crossed, and Carmella’s figure appeared in the window. She looked out, as if searching the sky for a sign.

“I think things changed,” she said, “when I saw Johnny Sketchy. I got a feeling then, of what I really want from a boy.”

“Augh, you too dreamy. But, what you feel, you need tell him.”

“He wouldn’t understand.”

Johnny Sketchy. Ian could picture the punk with that name: some skinny Wop who dodged the draft. Parades around in a zoot suit, hair slicked back with olive oil. Maybe a gold tooth. Well, Ian was going to find this Johnny Sketchy and set him straight. Carmella was his girl. His head pounded. His whole body felt heavy. A spell was coming upon him. He knew the feeling and knew he was powerless to stop it. So, he’d better go now, but he’d be back.

Morning dawned in a flash, and the Myrtle Avenue El train rattled Ian’s window. Seized by panic, he pressed the pillow to his face and ears, blocking light and sound. The train passed and Ian was himself again. He rolled to a sitting position, waited for the room to rebalance, then stood.

In the kitchen, his father and his uncle were reading the newspaper over coffee. As his mother placed steaming plates before the men, Mr. Sheehy sighed. “So, it’s yourself, is it?” he said, as always when, in his opinion, Ian had overslept. Ian mumbled, “Good morning.” He pulled a chair out to sit. Before his haunches even settled, his father had passed him the section of want ads. “Thanks.”

“Rheingold’s hiring,” his father said. “Preference to vets, it says.”

“I’ll look into it.”

“Less noisy than the docks, prob’ly.”

“’Til they blow that five o’clock whistle,” his uncle Bernie laughed. “Hey, they lookin’ for drivers? You wouldn’t be pent up inside.”

“Don’t be too particular.”

“I’m not being particular, Dad,” Ian said. His mother poured him some coffee and he nodded thanks. “I just gotta be where I can concentrate.” He reached for the spoon in the sugar bowl.

“You concentrate too much. All’s you need is something steady, then night school. Put that G.I. Bill to use. Pretty soon, you got a CPA and a nice quiet office.”

“I can’t think three years ahead, okay, Dad?” He knocked the bowl of the spoon on the lip of his cup, spilling the precious crystals onto the table.

“It’s a’right, Ian,” his Ma said, smiling gently. “Rationing is over.” He slid is cup aside and she wiped the table.

Ian looked at his hand, checking for tremors.

“You can’t think three seconds ahead with that Itie girl on your mind.”

“Leave her out of it. Please.”

“Plenty of girls at St. Barbara’s,” his Dad said. “No need traipsin’ ‘cross town for the hot-blood types.”

“Got Italians almost to Broadway,” Uncle Bern noted. “Six blocks away.”

“Be coloreds next,” his Dad said. “Soon’s the old Germans move out, you get Ities, then coloreds.”

“So what?” Ian said bitterly. “Their blood’s red. I’ve seen it.”

“Yeah,” his father said, folding his newspaper. He wiped his chin with a napkin and dropped it on his plate. “You fought your war, like a man should. Me and Bern, we fought our war, too. But we didn’t come home an’ lounge for a month and more. We went to work.”

“How many times do I…?”

“I know. You got headaches. I got ulcers. Bern, what you got?”

“Osteo arthritis.”

“The world doesn’t care.” His father rose and pushed his chair into the table.

Ian leaned back as his mother heaped his plate with eggs. “Enough, Ma, please.”

“Your mother cares,” his father said. “I care. The world doesn’t.”

The men plucked their hats and jackets from the hooks at the door. Ian stared out the kitchen window at a lemon sky and listened for the door to close.

After a few seconds, his mother asked, “Do you love that girl?”

“I don’t know, Ma.”

“Dolores Desmond asked about you.”

Ian let the remark pass. He tried a scoop of eggs. The headaches suppressed his appetite, but he knew he must eat to keep up his strength.

“I hate to say this,” his mother said, “but you’re wasting your time with that girl. She might be nice; she might be wonderful. I’ll admit, she’s beautiful. But, first, people prefer their own—”

“Ma—”

“And, a man needs prospects, if he’s going to win a girl.”

“I just won a war,” Ian said. “I can win a girl.”

She refilled his coffee. “Well, there you weren’t alone.”

I just won a war. That was a crock. The guys who spent weeks in field hospitals, then moved back to the front after the heavy fighting was over, after Mussolini and Hitler were crushed, they didn’t win the war. But Ian had ribbons on his uniform; he didn’t have to go into details. Carmella had been so proud to bring him home in unform to meet her father.

“You fought in a Italy?” Mr. Battaglia had asked.

“North Africa, then Italy.”

“Africa? You thinka they senda the coloreds. Their country….continent anyway.”

“Papa, be nice,” Carmella begged.

“I’m a just askin’, why they senda you there? You look a like a good sunburn a kill you.”

“Papa, no!” Carmella laughed, and music filled the room.

“Army never tells you why,” Ian shrugged. “But it was hot alright. Lots of sand.” He never understood what there was to fight and die for there in the desert. He nearly suffered heat stroke. Then Sicily, then assaulting the beach at Anzio. Before the war, Ian used to love Coney Island; now beaches meant combat, and he couldn’t even look at the sand.

“Well,” Mr. Battaglia tossed up his hands. “You gotta Mussolini out, da rat, and Hitler.”

Thus, he’d gotten the old man’s grudging respect. He’d asked about the ribbons, pointing to the red bar with narrow white and blue stripes.

“That’s for the bronze star,” Ian said.

“That’s a for a hero? Mama, we got a hero in the house!”

He made Ian tell him the story of Anzio. How, under enemy fire, Ian had picked up a fallen comrade and carried him forward twenty yards, fireman style, to drop him safely into a bomb crater. How he’d gone back ten yards for his lieutenant and dragged him to the same spot, easing him into the ad hoc shelter. He left out the part about being late to duck; how a shell detonated just yards away, knocking him unconscious for two days. Ian was never a soldier after that. For weeks, he was a patient. Then, just a working stiff, laboring in a support role, at one point assigned to a colored division. Those were facts he’d take to his grave.

He didn’t have to talk about the war to Carmella. She’d walked proudly through the neighborhood with her arm linked in his. And not just when he was in uniform. Even in his civilian clothes, a charcoal gray, single-breasted suit from Robert Hall, she’d said he looked like Gary Cooper. She’d been patient then. She loved to dance, but it was hard on him. The loud music, the crush of people, the frantic, boogie-woogie steps. When he’d had enough, his head splitting, she’d happily take some air with him.

One night, he got her to take a stroll through Prospect Park. Under the thick canopy of an old elm, he moved on her. They started to nuzzle. But he wanted to bury himself in her. To press into her hair, her cheek, her breasts, and rub the war away. She pushed and batted him off.

“I thought Irish boys were supposed to be nice,” she said.

“You like me, don’t you?”

“Sure. But I like me, too.” And she laughed that musical laugh of hers and tumbled into his arms again. He’d behaved himself the rest of the night. But the next time he’d seen her, she’d changed somehow. She didn’t explain and he couldn’t ask, but now he knew. It was Johnny Sketchy.

Ian went to the Rheingold Brewery that morning. Shouting to make himself heard above the din, he learned they wanted floor workers, not drivers. “You could ask at Schaefer,” the hiring man yelled. Ian walked the quarter mile to the competing brewery, where a fellow told him, “I might have something in a day or two.” He left his name and address, promising to check back tomorrow.

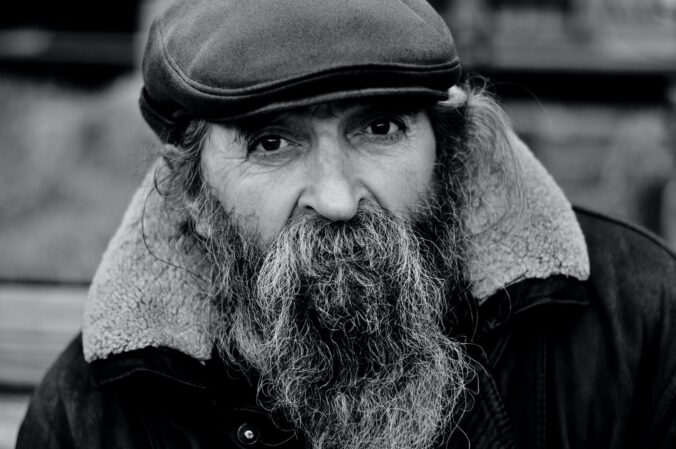

Ian spent the rest of the morning in Irving Square Park. He had a book to read, The Dangling Man by Saul Bellow, that the librarian had recommended, “for a boy in your position.” But the pressure behind his eyes made focusing on the small print impossible. He dozed on a bench until the tap of a cop’s nightstick on his thigh roused him. Then he walked. He visited a few more businesses who’d listed positions in the newspaper, but that was incidental to his path, due west, to the Italian district just below Brooklyn Heights, known inaccurately as South Brooklyn.

Ian arrived outside Carmella’s building just as the sun was dipping behind it. He wiped the sweat off his brow with a handkerchief and was suddenly self-conscious of his vapors. A day of walking, suited up in the warm sun, left him feeling rank. No matter; he wasn’t planning to get close to her. He only wanted to catch Johnny Sketchy.

Ian crossed the street and walked down the alley just far enough to see the Battaglia’s kitchen window. The curtains were open to get air flowing, and he could clearly see a slim, young man in a sand-colored suit. He held a broad-brimmed, whitish fedora in his hand. A thin mustache garnished a toothy mouth. Ian backtracked and trotted across the street. There was a coffee shop on the corner. He’d get a seat in the window and wait for Johnny.

It wasn’t long before his quarry emerged from the front door of the building. He donned his sharp fedora, and Ian noted the two-toned feather in the ochre band. Ian pitched his paper cup and went out to meet him.

“Hey,” he called while still some distance away, “you Johnny?”

The young man stopped and smiled, then looked over his shoulder, as if Ian meant someone behind him. He pointed to himself for confirmation. “John? No, no. Raphael.”

“You been to see Carmella?”

“I don’ think I need report to you my comings and goings.”

This guy was a weak sister. Skinny, hollow faced with the air of a fruit. What could she see in him?

“Listen, pal. Carmella’s my girl. Least up to a couple days ago. Now she’s got another guy on her mind. Johnny Sketchy?”

His mouth broke into a broad grin; the flimsy mustache faded as his upper lip stretched. The teeth looked too big for his mouth. He laughed briefly then waved Ian towards him. “Come, we go.”

“Where to?”

“I feel I am to blame,” he explained. “Because I introduce Carmella to who you call Johnny Sketchy. Now, I introduce you.”

Ian grabbed him by the lapel and wrenched him around. “What’s this, a set up? I don’t go for that, Joe.”

“Please,” he said, tapping a dainty finger on Ian’s clenched fist until he released his suit coat. Raphael smoothed his lapel and fluffed the kerchief in his pocket. “I’m a no Joe. Raphael. An’ I’m a help you. You see.”

They walked north briskly, though their progress was interrupted every few seconds, as this character encountered someone or other he apparently knew, prompting blessings and well-wishes for various family members before he could pry himself away and continue their trek. Eventually, they caught the Broadway Line east along Fulton Street. Still, Raphael greeted passengers getting on and assisted old ladies off. As the sun burrowed behind them, movie palace marquees lit up the distance. In his grandparent’s day, this had been vaudeville. Then in his parent’s time, silent films and early talkies. In Ian’s youth, technicolor was born, and he had sat transfixed before The Adventures of Robin Hood and Drums Along the Mohawk.

“Here is our stop!” Raphael said, pulling the signal cord. The streetcar screeched to a halt, putting Ian’s temples in a vice. He followed Raphael out the side door to the ticket booth of a stage theatre. A framed poster declared “The Sons of Italy of Bedford Stuyvesant present Giacomo Puccini’s one-act comic opera, Gianni Schicchi.”

“Is this some kind of joke?” Ian asked.

“Well, is a comedy.”

“That’s Johnny Sketchy?”

“Ski-key, mio amico. Is Italian.”

“Yeah, I got that.” But what Ian didn’t get was how an opera had suddenly turned Carmella cold towards him. The girl behind the glass slid two tickets forward. Ian reached for his wallet, but Raphael waved him off. “No, no, what is give free to me, I give free to you.”

“You’re connected with this outfit?”

“In a small way,” he answered, measuring a miniscule distance between his thumb and forefinger.

Things started to make a little sense. Him being artsy explained his dainty manners. He wasn’t anyone Carmella would fall for; probably a cousin, who had a theatre to fill. Ian followed him up a side staircase to the second level.

“Usu’lly, Puccini’s Il Trittico has t’ree parts. But we a small company; we only do t’e last one. Hope a you don’ mind.”

“Not at all.”

Raphael extended his left arm and lifted a black curtain, revealing a balcony box. He held the curtain as Ian stepped down, then they took their seats in the front row.

The floor seats were maybe half occupied. The orchestra consisted of two grand pianos, facing each other and pushed together ‘til their cabinets spooned. An elderly gent sat on a stool behind the far piano, shouldering a violin. The lights dimmed and two men in dark suits came out from the wings. They sat at the piano benches and rested their fingertips on the keys.

What proceeded was a lot of loud, thumping, dissonant nonsense. The curtains opened on a scene of ridiculously dressed villagers, all apparently mourning a corpse laid out in the center of the stage.

“T’ey are sing of t’eir grief,” Raphael whispered.

Me, too, Ian thought. Apparently, the dead guy had been very rich, and these were his relatives. They ransacked the stage looking for the old codger’s will. The kid who found it then seemed to want a favor from the rest, which none wanted to grant. A portly man entered with a young lady. While she made eyes at the kid who found the will, the portly gent seemed to offend the mourners. They flew into high dudgeon, and he wrenched his daughter from the boy.

That roused the sleeping violinist who sawed his bow across the strings, buzzing like a low flying plane. The cast froze, like waiting for bombs to drop. Instead, the girl opened her mouth, with a voice like the morning sun.

“O, mio babbino caro…”

Her breath brought a breeze into the room, lifting the thin, white curtains, so Ian could see the church steeple across the piazza. He was delirious again, hanging somewhere between sleep and waking, gripping the straw mattress, as Alba bent over him.

“mi piace, è bello bello, vo’andare in Porta Rossa, a comperar l’anello!”

Enchanting tones teased the air, defying the earthbound scratches of an old Victrola, inviting celestial light to flood the space. And Alba stroked Ian’s forehead with a cool cloth. His eyes focused, and her perfect face took form.

“Si, si, ci voglio andare!”

Her olive skin, the sunlight shimmering off her bare shoulders, black tresses tumbling, and her sculpted, pink lips pursed in sympathy.

“E se l’amassi indarno, andrei sul Ponte Vecchio, ma per buttarmi in Arno!”

Ian hadn’t forgotten Alba, but neither had he remembered her so vividly as now, in the throes of this aria. She had played it repeatedly on her father’s Victrola, during the weeks Ian had convalesced at their farmhouse. He’d never asked what the words meant, but had understood them as a plea for love unto death.

“Mi struggo e mi tormento…”

The girl’s voice soared and glided, lightly as a feather on the wind. And Ian saw Alba for the last time, from the back of a jeep, as she left the church after morning Mass and the breeze lifted her chapel veil. She’d swiped her hand after it, but the white lace kite had flown. Towards Ian, he thought at first. What a sign that would have been. But it sagged and came down where a sergeant grabbed it and gallantly returned it to her. Alba thanked him, then searched the departing soldiers until she caught Ian’s eye. In a movie, or an opera, they’d have run to each other, thrown themselves into ready arms. But somehow there was a gulf between them that swallowed up all emotion. All impetus. Ian felt the Jeep lurch and it rolled away, expanding the distance between them until their connection snapped.

“O Dio! Vorrei morir! Babbo, pietà, pietà! Babbo, pietà, pietà!”

The soprano’s voice diminished, the airy stream holding her hopes aloft dispersed, and she slumped at her father’s feet.

The crowd erupted. Ian clutched the heels of his palms to the boney rims of his eyes. He pitched forward, rose from his seat and staggered through the exit.

Out on the street he could breathe again. Yet, still in the dark, he felt Alba’s presence. Her scent of lavender. Her light, cooling touch, wiping the war from his burning brow. “My angel of mercy,” he’d called her. “No,” she had smiled. “You not see the angels for some time, I hope.”

With that, Ian noticed Raphael standing beside him.

“That song affect Carmella, too,” Raphael said. “Same way, I think.”

“You think? What do you know?”

Raphael shrugged, politely conceding he didn’t know anything. But that didn’t stop him from talking.

“She like you, but she no unnerstan’ jou.”

Ian smacked him in the shoulder. “Can you quit it, huh?” He needed time to think. And quiet. Which of these girls was he in love with? Either, really? Was he stuck on Alba and trying to make Carmella into her? And when Carmella couldn’t … couldn’t wipe the war away, he’d… he’d felt distance between them, the distance of a Jeep pulling away into oblivion, and he’d forced that distance to close, he’d pulled her to him, and…. What had he done? He’d handled her like some brute.

Raphael was still hanging around. Ian reached over and patted him on the shoulder. “Sorry. Maybe I don’t understand myself either.”

A dark cloud of shame enveloped him. He’d thought he was fortunate, that his wounds weren’t visible. Nobody seeing him on the street would show pity in their eyes. But a visible wound was at least tangible, comprehensible. He couldn’t explain how he was to himself; how could he ever make Carmella understand? She wanted a hero, and he felt hollow.

He searched Raphael’s eyes. Dark, walnut orbs, they were too large and sensitive for a man. At once, they begged to be trusted and warned of a trap. If this guy was queer, anything Ian told him would be all over the borough tomorrow. Still.

“You said Carmella likes me. You mean maybe she loves me?”

His lower lip bulged upward, drawing the corners of his mouth down in a clownish mask of ambiguity. “She might, I think, but she…”

“What? What did she say?”

“She say you, uh, sketchy.”

It took a moment, but Ian began to quake, not in anger, but with laughter. Uncontrollably, his insides shook, and he pitched his head back as wave after wave escaped. He almost lost his balance, and would have staggered into a passing couple, if Raphael hadn’t pulled him away. He didn’t know why it struck him so funny, except it was true. Ian Sheehy was Johnny Sketchy. An insubstantial man, drawn of lines, missing color. Without substance.

“But jou know,” Raphael mused, “all the great masterpiece, they start with a sketch.”

Ian clapped Raphael on the shoulder again.

The war had robbed him of color. Alba had washed away some darkness and let some light in. But clouds had crept back and maybe always would be there. Now it was up to Ian to restore the color, maybe with sunlight and music. And love. Maybe with Carmella, and maybe not. He would see about that. He’d go to her and explain. And if it didn’t work with Carmella, there were other girls, who might be patient and kind, and he could be a good man for one of them. Today he was Johnny Sketchy, but someday… there would be color and shape and substance. The stuff of life and love.

If you enjoyed this story, please explore this website for more fiction choices, such as The Wedding Routine, which Online Book Club calls an “amazing book” with “dynamic characters” who “produce nothing but comic gold.” Or visit my Amazon author page and consider purchasing one of my books. You can also support this website by clicking on an affiliate link and making a purchase. For example, the Product of the Week, featured below. When you click and buy anything at all in the next 24 hours, the website receives a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for your support.

Product of the Week

Yamaha, 61-Key PSR-E273 Portable Keyboard

When the world shut down for Covid, and I couldn’t continue with dance classes, I decided to teach myself to play piano. This keyboard was the perfect starting point. Great sound, and the volume controls made it perfect for apartment living. So lightweight, I was able to travel with it easily, so I didn’t have to interrupt my practice when I was on the road bouncing from one airbnb to another. Lots of amusing functions that I barely used. Its “weighted keys” are not really the same as a piano, but it got me ready for the beautiful Charles R. Walter upright I now own. Altogether, a great beginner’s instrument. Kevvy says, “Check it out.”

Recent Comments