Author Kevin Rush drops some clues for literary sleuths

I’m far from an aficionado of the mystery genre, so I’m probably late to this party. But when I learned that Private Eye July was an actual thing, I laced up my gumshoes, loaded my snub-nosed .38, and doffed my gray, felt fedora. Hot on the case, I pursued several suspects that might pay off with a guilty pleasure. It’s sometimes tough to cut through the thick fog of saturated bookshelves and eliminate the red herrings . And a month is not long when it comes to consuming whole novels. I didn’t want to throw days away chasing dead ends. But I didn’t want to play it too safe either by treading overly familiar territory.

Now that PI July is over, I figure I got more or less what I wanted from the dust jackets I frisked and the pages I flipped. That being a concise narrative told in an engaging style with vivid characters, intriguing twists, and a satisfying resolution. So without further palaver, here are the novels of my PI July.

Black Money by Ross Macdonald.

This is the 13th of Ross Macdonald’s 18 novels in the popular and critically acclaimed Lew Archer series. Archer is also featured in nine short stories. A native of Southern California, operating from the late 1940s to early 1970s, Archer is something of an heir apparent to Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, who roamed Los Angeles in the 1940s. Equally world-weary, Archer is nevertheless smarter and more empathetic than Marlowe. We’re told he served in U.S. Army Intelligence during WWII, was briefly a Long Beach, CA cop, was married at some point, and values his independence.

Black Money, published in 1966, is the third Archer novel I’ve read. A couple of years ago, I picked up a collection entitled Archer At Large (1970). So, by now, I had already read and enjoyed The Galton Case (1959) and The Chill (1964). Macdonald is adept at weaving intricate plots, but what I really like is his economical style which is simultaneously terse and rich. As a narrator, Archer has a knack for relating his observations of behavior in terms of character, so we understand who the players are and what motivates them. The books are peppered with references to philosophy, psychology, and literature, lending the characters and their dilemmas an archetypal resonance.

The Archer novels are more than puzzles; they’re intricate human dramas. William Goldman, writing in the Book Review section of The New York Times, stated that the Archer books are “the finest series of detective novels ever written by an American.” More than a mere genre writer, Macdonald is generally recognized as one of the best American novelists of his generation.

We won’t get deeply into the screen adaptations of Macdonald’s Archer books. Suffice to say that Paul Newman (Harper, 1966) had the blue eyes of the character, but little else. Archer is described as a lean and rangy six foot two, capable of handling himself against menacing baddies. Newman was notoriously short, with a large head that ample goons could easily use as a speed bag. Though he played a middle-weight boxer convincingly in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), Newman’s most famous onscreen dustup came in a brief knife fight with no rules.

My choice would have been Robert Mitchum. In the mid-1960s, Hollywood’s first King of Cool could have played mid-series Archer. But, the choice was made to start with the first book The Moving Target (1949), and Newman was a star in his prime.

A couple of reasons have been given for changing the PI’s name from Archer to Harper in Newman’s films. The most credible one is that Macdonald had named his character for Miles Archer, Sam Spade’s deceased partner in The Maltese Falcon, and somebody had been hypersensitive of the potential for copyright disputes.

Harper was a hit, but it was nearly a decade before Newman filmed Macdonald’s second Archer novel, The Drowning Pool (1950) in 1975. Newman was a little busy making better movies, such as Cool Hand Luke (1967), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1974). A third Archer book, The Underground Man (1971), was made into a television movie in 1974. It starred Peter Graves, who is much more the Archer type.

I highly recommend the Archer series, but I’d advise you to start at the beginning.

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman by P.D. James

In this 1972 novel, British writer P.D. James introduces Cordelia Gray, a novice sleuth who inherits her mentor’s detective agency after he abruptly commits suicide. Her first case is an apparent suicide, which provides her with all sorts of mixed feelings, which she must work through to complete her assignment. My previous exposure to Ms. James was limited to her novel, Children of Men (1992), and its film adaptation (2006), which I blogged about here.

I found Unsuitable Job very engaging. It went deep into Ms. Gray’s character, as she fended off doubts based on traumas in her past and faced present dangers. But I never sensed there was too much “processing” of her feelings, and I liked seeing the growth in her character. The way Cordelia Gray steels herself against her own frailty is the perfect antidote for today’s tiresome girl-bossery. Ms. James only wrote one more Cordelia Gray mystery, which strikes me as a shame. The character had a bit more of a life on television; four movie-length episodes of a series were shot over two seasons. A 1982 film version of Unsuitable Job was not well received.

Ms. James’ primary detective is Inspector Adam Dalgliesh, for whom she wrote 14 novels. He appears in Unsuitable Job.

Devil in a Blue Dress by Walter Mosely

This 1990 novel gives readers their first look at Mosely’s amateur detective, Ezekiel (Easy) Rawlins. Most folks are probably aware of the song Devil with a Blue Dress On, which contains a vamp with the line, “Devil in a blue dress, blue dress, blue dress.” Written and recorded for Motown in 1964 by Shorty Long, the song failed to chart. Two years later, Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels paired it in a medley with Good Golly, Miss Molly, and their single hit No. 4 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100. Bruce Springsteen covered the Ryder version in 1980 at the No Nukes Concert in Madison Square Garden.

However, the song has nothing to do with this book, which is set in 1948. So, I’ve got a little bone to pick with Mr. Mosely about his anachronistic cultural reference. Fortunately, that’s about all I have to quibble with.

The book is told mostly in a spare style, with just enough description filtered through Easy’s wry observations. However, Mosely knows when to elaborate and even when to wax poetic. Easy is a bright everyman, good hearted but far from saintly. He’s also a WWII combat veteran with just enough PTSD to be lethal and maybe even his own worst enemy. The characters Mosely throws in with Easy are varied and believable. The story is well-paced, at times gripping and surprising, and resolves well. We’re left wanting to join Easy on another case. My only other (minor) gripe is that I had a little trouble keeping the characters straight. That might be a lack of exposition, or it might just be a me problem.

I’m sure many people have seen the 1995 film version, starring Denzel Washington. I haven’t seen it in 30 years, and I recall it being an okay thriller, but nothing too special. It did not turn into a franchise opportunity for Denzel. That’s perhaps a shame, since there are 16 Easy Rawlins novels to date that might be adapted.

This is where I say, give it a read even if you’ve seen the film.

Lady, Go Die! by Mickey Spillane and Max Allan Collins

I was going to read Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury, to get an introduction to PI Mike Hammer. But I couldn’t get my hands on a copy. Instead, I settled for its “posthumous sequel.” Apparently, when he died, Mickey Spillane had a slew of unfinished Mike Hammer novels laying about. The task of completing these fell to Max Allan Collins, a prolific crime fiction writer perhaps best known for the graphic novel, Road to Perdition.

After 84 pages, I put this one aside. It was a little over the top for me. One of the cardinal rules of tough guys is they don’t go around proving they’re tough. This rule gets broken in the most cartoonish, buffoonish manner possible. Hammer, in the middle of a police station, goads a few cops into a fight and then shoots a gun out of one of their hands. This guy literally shoots up a police station and the cops let him walk out with a warning.

I’ve got a few more weeks on the library loan, so maybe I’ll pick it up again. But as of now: Zero stars. Would not recommend.

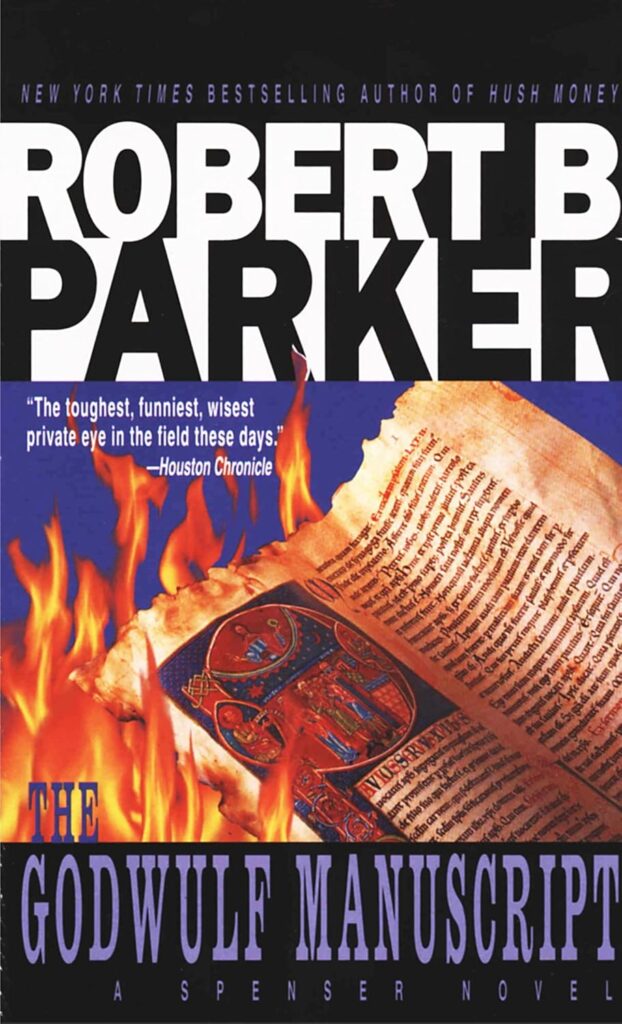

The Godwulf Manuscript by Robert B. Parker

Published in 1973, this is the first of 40 Spenser novels from the prolific mystery writer who also gave us Jesse Stone. The fictional Boston PI first came to my attention with the 1985 TV series Spenser: For Hire, starring Robert Urich. I wasn’t watching much TV in those days, and after a childhood saturated with Quinn Martin Productions, it was hard to get excited about a new detective show. Elvis Costello could have written his song about my mother, because she was always, “Watchin’ the detectives.” Columbo, Dragnet, Cannon, Barnaby Jones, Mannix, Kojak (“Who loves ya, baby?”), The Rockford Files, Baretta, Peter Gunn, The Mod Squad, and The Streets of San Francisco.

Then, in 1981, cop TV changed forever with the advent of Hill Street Blues. Steven Bochco’s groundbreaking series ushered in stark realism, overlapping storylines, and a huge ensemble where every character, no matter how apparently inconsequential, was fully fleshed out. Spenser: For Hire might have been better than standard 70s fare. But after Hill Street, it struck me as retrograde, a return to simple plots, flat dialogue, and pat endings. I didn’t give it a chance.

However, while I was searching for another PI to try, the sheer volume of Spenser books caught my attention. I found a collection of the first three books entitled Enter Spenser, and I dove into The Godwulf Manuscript.

Firstly, this book is steeped in the 70s culture of sex and drugs and college radicalism. It mostly takes place on a university campus, a milieu which Parker knew intimately as a Northeastern University professor. Spenser is a relatable protagonist. Charming when he needs to be, but not suffering fools patiently. Some of the lip he gives authorities comes off as gratuitous, and a fair number of his quips don’t land. Of this latter point, Parker seems aware. On more than one occasion, he has a character comment on Spenser’s wit, as if that validation will get us readers to play along. But, all in all, the story was well plotted, moved at a brisk clip, and was resolved satisfactorily. I’m not a terribly fast reader, but I sped through this book. Now, since I’ve got two more Spenser novels chambered, I’ll probably give him another shot.

Interestingly, I learned that Parker completed an unfinished 1958 Raymond Chandler novel, Poodle Springs, published in 1989. (Chandler had written the first four chapters.) Then in 1991, Parker published his own Marlowe novel, Perchance to Dream, a sequel to The Big Sleep. This one has me curious. Maybe we finally learn who killed the chauffeur.

So there it is. My complete book report from Private Eye July. Now, what about August?

Revitalize Your Smile with Larine!

Sensitive teeth? Dull smile? Revitalize your smile by re-mineralizing your teeth. Larine has a revolutionary line of oral care products from tooth paste to chewing gum fortified with hydroxyapatite to restore enamel. Your teeth are alive and capable of healing themselves (even repairing cavities!) if you treat them to the natural compounds they need. Use this link to visit Larine, and get 10 percent off every order.

Disclaimer: This column contains affiliate links. When you click on an affiliate link and make a purchase, this website receives a small commission at no extra cost to you. We thank you for your support.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.