Why it’s more important than ever to honor the North American martyrs

In my childhood, priests were heroes, and the Jesuits were the mightiest among them. I recall my first-grade teacher, a Sister of St. Joseph, telling us, “If you saw one of the Fathers walking on the sidewalk with an angel beside him, you should say hello to Father first.” In fourth grade, I was tasked, along with a classmate, with writing a play on the life of St. Isaac Jogues for our American history class. I was awestruck by his willingness to suffer such cruel torture for the sake of the Gospel. And I was proud that a member of my family, my father’s cousin, was serving as a Jesuit missionary in Hiroshima, Japan. I wanted to study with the Jesuits, to be molded by them.

Well, the ensuing decades have not been kind to my early impressions. Widespread corruption, political machinations, and none-dare-call-it-heresy have scorched the bloom off the rose. But given that Tuesday, October 19 is the Feast of St. Isaac Jogues and Companions, I decided to drive up to The Shrine of the North American Martyrs for a few hours of prayer and reflection on those eight men whose lives so perfectly exemplified Our Savior’s command to “pick up your cross and follow me.”

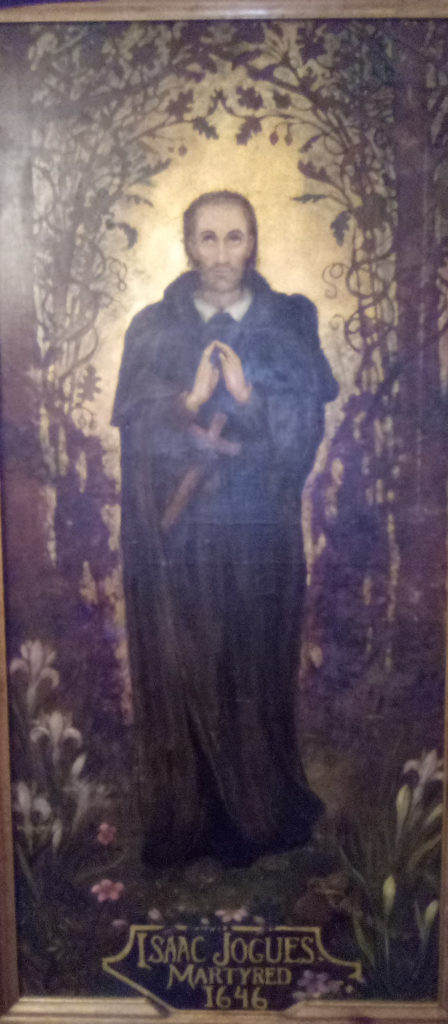

The Shrine, built on the grounds of the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, has a Coliseum Church built in the round. Its brick exterior resembles a small college football stadium, while the rustic interior is decked out in timber in imitation of frontier forts. The square Sanctuary has altars on four sides dedicated to three Jesuits—the priest Jogues, and the laymen Rene Goupil and Jean de Lalande—who were killed in the vicinity, and St. Kateri Tekakwitha, a Mohawk maiden, who was born in the village. The grounds, with memorials to the martyrs and paths for walking the Stations of the Cross and the Seven Sorrows of Mary provided ample opportunity for reflection. The old awe returned.

In The American Jesuits, a History, Raymond A. Schroth. S.J. writes that Isaac Jogues, a native of Orleans, France had entered the Jesuit novitiate in Rouen at 17. Though “small, delicate, sharp-eyed and fine featured,” Jogues passionately sought the most rigorous vocation: preaching “simply to the ‘savages’ of the New World.” Fr. Schroth describes how Jogues, at 29, arrived in French Canada:

“On August 14, 1636, young Fr. Jogues gazed up the [St. Lawrence] river in awe as a flotilla of Algonkian canoes heaved into sight. The savages brandished 28 scalps from their poles…. They had two prisoners—an Iroquois brave standing tall, proud, and naked in the canoe, and a native woman. As they pulled into the landing, the native women, many of whom had thrown off their clothes to swim out to the boats, surrounded the native prisoner, beat him with clubs, ropes, and chains, stabbed him with burning sticks, and crushed his fingers in their teeth. One who cut off his thumb had tried to force him to swallow it. When he failed to choke it down, she cooked it for the children to eat.”

Jogues had been forewarned of savage practices. The missionary Paul Le Jeune, S.J. had written in 1632 describing how captors inflicted “all the cruelty that the devil can suggest” on prisoners, culminating in cannibalism. Le Jeune warned that if the Iroquois captured his brother missionaries, “we would be obliged to suffer this ordeal.”

Jogues’ ordeal began on August 2, 1642, when on a return journey from Quebec, a force of Iroquois overwhelmed his Huron escort. Jogues had his chance to escape, but seeing Goupil captured, he surrendered rather than abandon his young companion. For three weeks, the Iroquois “paraded their 22 captives [naked] through the countryside,” stopping at various villages for rounds of torture. Sensing that Jogues was the leader, they abused him particularly. Natives “hacked off his left thumb and chewed his fingers to the bone.” (Jogues would later have to get special dispensation from the Pope to say Mass, since priests were only allowed to touch the consecrated host with thumb and forefinger.) Jogues and Goupil eventually found themselves in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, basically enslaved, but treated kindly by “some women.”

Goupil met his fate when he imprudently made the sign of a cross over a child, which an elder took to be a curse. Jogues then witnessed a hatchet splitting his friend’s head. Living largely on corn meal because meat in the village was offered to the devil before consumption, Jogues wasted away. However, he spent abundant time in prayer and reconciled himself to captivity, since his ministrations were a comfort to many, and he had managed to baptize “more than 60 persons.” Then, informed on August 18, 1643, of a plot to burn him alive, Jogues escaped and returned to France.

For most of even the holiest men, that would have been enough. But in less than two years, Jogues was back in New France. Again, he was captured, again with a lay Jesuit companion, Jean de Lalande, and brought to Ossernenon. One of the clans called for his death. They lured him to a lodge, promising to listen to him, but struck his head with a tomahawk as soon as he stepped through the door. Both Jesuits were decapitated, and their heads placed on display.

It’s easy to argue that Jogues was imprudent. His own superiors urged him to stay among the docile natives, where his labors could bear abundant fruit. But in risking all to reach out to the hostile tribes, Jogues embodied Christ’s sacrifice as Paul describes in Romans 5: 6-8:

“Indeed, only with difficulty does one die for a just person, though perhaps for a good person one might even find courage to die. But God proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us.”

Fast forward some 240 years, and a different definition of Jesuit martyrdom begins to emerge. On November 16, 1989, a force led by Lieutenant Ricardo Espinoza, acting on orders from Colonel René Emilio Ponce, chief of staff of the Armed Forces of El Salvador, executed six Jesuit priests. They also killed two women witnesses, then tried to make the attack look like a Communist reprisal. Forces on the Left, with whom the priests were more than friendly, suddenly found religion, charging the Death Squads with the unthinkable crime of priest killing. The story went out that the Jesuits had been killed, because of their advocacy for the poor. They were martyrs. But not so fast.

The war in El Salvador had no good guys. Establishment forces were propping up a ruthless oligarchy that cruelly subjugated and exploited the poor. On the other hand, the insurgents were Communists supported by the Soviet Union looking to enslave the nation under Marxism. But instead of declaring a pox on both their houses and calling each side to the truth of the Gospel, the Jesuit intellectuals under Ignacio Ellacuría, president of the University of Central America in San Salvador, embraced the Communists. Somehow they had missed Divini Redemptoris, the 1937 encyclical by Pope Pius XI in which he declared “Communism is intrinsically wrong, and no one who would save Christian civilization may collaborate with it in any undertaking whatsoever.” Did Ellacuría et al. also overlook Communism’s 20th century’s global death toll? Or did they believe with characteristic Jesuit hubris that they could use an intrinsically evil system for the greater glory of God?

In adopting Liberation Theology, a twisted dogma that perverts Catholic social teaching and subordinates salvation through Christ to economic achievements, Ellacuría and comrades acted not as priests but apparatchiks, lending legitimacy to the Communist insurgency. It’s as though Jogues had gone over to the Iroquois. They corrupted the UCA to pump out Communist propaganda. They abandoned their roles as shepherds and peacemakers to exacerbate tensions in the ongoing war, all the time imagining their black robes made them bulletproof.

That’s not to say the Jesuits were legitimate military targets, and only a regime cribbing the Francisco Franco playbook for Communist annihilation would have dared attack them. Ultimately, the priests were victims of a war crime. They may even have been martyrs to “The Revolution.” But suggesting they are martyrs to the Gospel of Jesus Christ is cheap propaganda that taints the legacy of genuine martyrs like Jogues whom we must continue to hold in the highest esteem.

Since 1989, the downward spiral of the Society of Jesus has only accelerated. We now have a Jesuit pope who embraces every far-Left initiative from assorted dastards dedicated to a pantheon of anti-Christian causes, including abortion on demand, euthanasia, and sterilization. Having forgotten the lesson of Fr. Jogues, the Pope joins hands with pinstriped neo-paganists who would not only bite his hand, but gnaw his fingers to the bone. Meanwhile, formerly vaunted Jesuit institutions cover up crucifixes so as not to offend pro-abort politicians and corrupt their students with Critical Race Theory, a Communist doctrine so pernicious it makes Liberation Theology look downright Thomistic. And a periodical acting as the organ for Jesuits in the United States deigns to publish a turgid, ill-reasoned and historically illiterate apologia, entitled The Catholic Case for Communism.

In light of these circumstances, it’s crucial that we remember and celebrate the lives and sacrifices of the North American martyrs, who are the antidote to and the eyewash for the corrupting campaigns within the Society of Jesus today to bend the church towards the material world and hand out martyrs’ crowns where pity is the more profound response.

This summer I also had occasion to visit the National Shrine of Elizabeth Ann Seton, which I comment on here. Below is suggested reading for Catholics of all ages on St. Isaac Jogues and other American martyrs.

Disclaimer: Links in this column may be affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link, the author receives a small commission on purchases for a limited time at no additional cost to you. These commissions help ensure future posts. Thank you.

Recent Comments