My unexpected rendezvous with a saint I already should have known

I don’t like being stuck in traffic. Who does? So when my digital GPS lady warned me about a tie-up on I-81 and offered me a diversion onto U.S. Route 15 South, I took it. Just to keep moving towards my goal for the day, a cozy AirBNB room on a farmhouse at the lower end of the Shenandoah Valley. That’s where my quest for history was scheduled to start, with a few battlefield markers, remnants of Stonewall Jackson’s legendary campaign. But as so often happens, God had other plans, and for me that meant encountering a different hero.

After about 20 minutes on Rt. 15, I saw a brown sign for a point of interest: the National Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton. Since it was right along my way, I decided to make the stop. I’d stretch my legs, make a courtesy visit to the Blessed Sacrament, and maybe get a few snapshots of a nice-looking church. I’m a huge church nerd when I travel. I feel they tell the people’s history, their devotion, their struggle for a better life, better than any collection of museum artifacts. But I had low expectations for Mother Seton, especially out in the nowhere of Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Did I know who she was? Vaguely. I was in eighth grade at St. Aloysius School in Jersey City, NJ in 1973-4 when the drive for her canonization had reached a fever pitch. She would be the first American-born saint in the Catholic Church. The nuns were elated; they were Daughters—or Sisters—of Charity, and Mother Seton had been their Foundress. But we students, at least at the too-cool-for-school junior high level, didn’t share their euphoria. Not that I had anything against nuns generally or Sisters of Charity in particular. They didn’t hit us like the Sisters of St. Joseph in Bayonne had, but they were boring ladies living dull lives. They taught grammar school all day, then went back to the convent to grade papers while watching The Mod Squad, and who knows what they did during the summer? Now, tell me Roberto Clemente is going into the Baseball Hall of Fame, a player I watched on TV and in person, whose death I read about in the sports pages and even cried over, that’s the kind of induction that would mean something to 13-year-old me.

Plus, there had been an unfortunate changing of the guard at our school. We’d gotten a new principal the previous year, who had canceled a few vaunted traditions, such as honors at graduation. I didn’t care; as a bespectacled runt at the head of the class, I preferred to downplay academics and score social points as a joker. But some kids on the cusp of smartness would really like to have had their smartness affirmed in some small way. Then there was the Spring Musical, an elaborate production which the previous principal had staged as a fundraiser. Every musical number sung by the leads got an encore by a particular class. Thus, every student in the school appeared on stage and parents packed the gym-auditorium to glimpse their little darlings. Well, the new principal put the kibosh on the extravaganza after a dismal staging of The Red Mill flopped badly. There would be no musical for my graduating class. Our Eight Grade teacher, Sister Barbara Ann, not the inspiration for the Beach Boys, offered a compromise: we could do a small play on Mother Seton.

I still remember Connie D. huffing as she pushed past me in crimson indignation, “Every class gets a musical; we get Mother Seton!” I don’t know whether Connie had set her heart on playing Dolly Levi, but she didn’t want the parade to pass her by, and in her mind, Mother Seton had just rained on it. Again, I was totally neutral. For one thing, my lovely boy soprano had gone rogue last year, and I never knew when Alfalfa would show up. For another, I had played Friedrich in The Sound of Music in sixth grade, which had been enough. I still remember Sister Catherine Maurice, who had not studied Stanislavski, bellowing, “You can’t cross in front of her, she’s a lead! Cross behind! There’s no crossing in front of a lead!” and the tearful girl answering, “But then no one will hear me!” It was not an experience I yearned to repeat. The matter soon became moot, as Sr. Barbara forgot all about the Seton play, and the students didn’t dare remind her.

In the fall of 1975, I vaguely remember time set aside to celebrate Mother Seton’s canonization. But aside from “First American Saint,” I don’t recall the Jesuits at my high school filling us in on any details. Maybe there was some chauvinism in the slight. If we wanted inspiration from a saint who had founded an order, we already had St. Ignatius. Mother Seton was a nun who had founded an order of nuns. End of boring story. But how wrong. And how tragically so.

What I found at the Shrine was the life story of a courageous woman, whose courage was at turns genetic, instilled and grasped for desperately at the edge of despair. Elizabeth Ann Bayley was the daughter of a crusading New York physician Richard Bayley, who fought heroically to curb yellow fever outbreaks that periodically ravaged quarters of Manhattan. He travelled to England to study infectious diseases, and returned with vital information about draining swamps to reduce mosquito-borne contagion. Dr. Bayley succumbed to yellow fever, but his work saved countless lives.

Elizabeth’s mother died when she was three, perhaps from complications of childbirth. Her stepmother brought her on charitable rounds, delivering food to the poor. She eventually separated from Elizabeth’s father, taking the five children of their marriage and rejecting the two children of his first marriage. Thus, Elizabeth’s early life was marked by painful separations, a trend that was destined to continue.

In 1794, at the age of 19, Elizabeth married William Magee Seton, a wealthy but sickly trade merchant. His business declined as Jefferson’s embargo on trade and the subsequent War of 1812 devastated the overseas shipping industry. But the worse decline was in his health; as tuberculosis ravaged Seton’s lungs, he desperately sought a cure in the fair climate of Italy. Elizabeth was at his side throughout, reading her Bible and praying ceaselessly. At age 29, she became a widow with five children and no visible means of support. Yet, encouraged by Italian friends, the Protestant Elizabeth felt the call to convert to Catholicism, which she did upon her husband’s death, even though it meant ostracism from a family network that could provide financial support for herself and her children. That decision also placed her in real physical danger, as evidenced by a Protestant attack on her Catholic Church. On Christmas Eve, less than two years after her conversion, a mob was thwarted in its attempt to burn the church.

I could go on. About her children who also died from tuberculosis, and her personal struggle with the disease that took her at age 44. And how in spite of all that was bleak around her, she maintained the optimism and drive to found a religious order in a country where Catholicism was widely reviled. At the tender age of 13, when I was so much more certain about what I knew than I am now, I wouldn’t have granted much credit for starting an organization or keeping it running despite financial hardships. In the years since, I’ve gained an appreciation for those leadership and administrative skills that I sorely lack, and which are sorely lacking in society as a whole.

All of what I saw at the Shrine made me grieve for the lukewarm catechesis of my formative years. I had been reared on heroes, real and fictional. I idolized Patrick Henry, Robin Hood, King Arthur, Davy Crockett, Abe Lincoln, Jackie Robinson, and the aforementioned Roberto Clemente, who in my lifetime died tragically attempting to deliver relief supplies to impoverished earthquake victims. But in my formation, the heroism of saints got short shrift. They were generally portrayed as well-behaved, pious and dull, maybe because that’s how our parochial schoolteachers would have preferred us. But how much more enriching it would have been to have been told the gritty details of Elizabeth Ann Seton, how she had fought the perils of this Earth to beat a path towards her and our eternal reward?

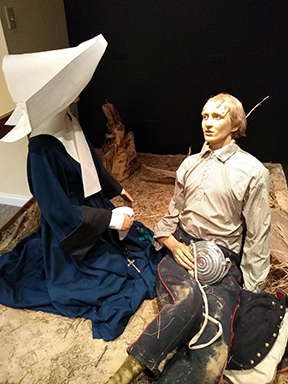

I was heading to Shenandoah hoping to rekindle my fascination with Stonewall Jackson and his display of tactical brilliance in a lost cause. What I found was a tactically brilliant saint who fought for a winning cause and whose legacy lived on in the women her convent schools trained as nurses and teachers. At the outbreak of the Civil War, 600 battlefield nurses had been commissioned, all of whom were Catholic nuns. Somewhere Elizabeth Seton must have been smiling as her sisters responded to the red landscape of Antietam to nurse the wounded of either side. These “angels of the battlefield” labored tirelessly in an era of bone saws sans antibiotics to give young combatants comfort when they were beyond hope. Among the casualties was a captain of the Forty-first New York Volunteers, French’s Division, Sumner’s Corps. His upward gaze at his angel of mercy must have had profound meaning. For his name was William Seton III, and he was the grandson of Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton.

There’s a saying I’ve heard often lately, that no one goes to hell or heaven alone; wherever we go, we take others with us. That’s why one saint’s canonization should be a moment of joy for all believers. And as Christians, we should share that joy at every opportunity, especially with the young who don’t know what they don’t know.

For your consideration:

To learn more about St. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s life, legacy and writings, click this link.

Disclaimer: Links in this column may be affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link, the author receives a small commission on purchases for a limited time at no additional cost to you. These commissions help ensure future posts. Thank you.

Recent Comments