The field was once Rich; now there’s Little worth imitating. By Kevin Rush

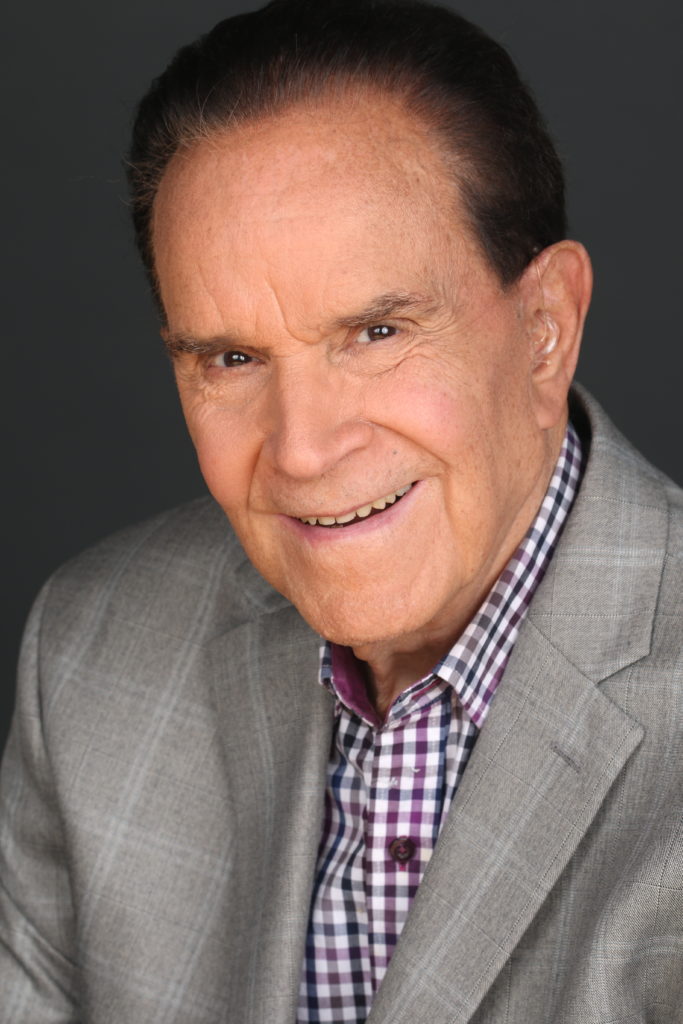

In July, I had the pleasure of meeting Rich Little, the famous TV and nightclub impressionist who had been so popular during my youth in the 1970s. Those of us gathered for the intimate event spent the first hour before his arrival reminiscing about his many appearances on The Tonight Show, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, The Hollywood Squares, The Mike Douglas Show, Here’s Lucy, and countless other TV shows.

We recalled the many celebrities he had impersonated: John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Carol Channing, and especially his bread and butter, Richard M. Nixon. In fact, Mr. Little was in NYC to portray Nixon in an Off-Broadway play (a rare bird in this age of COVID), called Trial on the Potomac, which imagines the impeachment proceedings for the president who refused to step down amidst the Watergate scandal. That Mr. Little was still playing Nixon struck me as quaint, but it also provoked a rather uncomfortable thought: if Rich Little were starting out today, talented as he was, he would starve to death. The reason is two-fold: there is no one to imitate, and everyone takes offense.

In this post, I’ll deal with the first issue. For the last 40 years at least, there has been a serious problem in Hollywood in the development and promotion of what we used to call movie stars. Paul Newman saw this problem coming in the 1970s, when he lamented that the biggest box office stars were two robots and a mechanical shark. Certainly, trends in movies—reliance on CGI and pyrotechnics—have stunted the development of actors, who might have otherwise achieved some level of stature, but acting training has had a great deal to do with it as well. Over the last several decades, actors have not trained for the stage; they’ve entered whatever acting academy will take them, focused entirely on television and film style acting, which emphasizes naturalism to a fault. As a result, they don’t develop their voices, and those voices never become distinctive.

I remember reading David Mamet’s intelligent 1987 collection of essays, Writing in Restaurants, in which he argues “Against Amplification” in live stage theatre. He posits that amplification robs the audience of the richness of a trained voice, which is a glorious part of the theatrical experience. Amplification has led to decadence in vocal training. Fast-forward 34 years, and I can barely make out what TV and film actors are saying, especially when the cine-luxe auteur has decided to mix the soundtrack music above the vocals, as if it were all one lush wave of sound or a singular grunge-fest growl. Yes, I’m looking at you, Tom Hardy in The Revenant.

But getting back to my original point. Of course, Rich Little is still doing Nixon, because no one would know who he was doing if he did Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling, Bradley Cooper, Ben Affleck, Robert Downey, jr., or that guy who plays Wolverine. And it’s not that they’re bad actors (okay, Affleck, yes), it’s just that there’s nothing distinctive about their light, breathy, underdeveloped voices. Moreover, as actors, they’ve been trained to be chameleons rather than icons, the better to expand their range and marketability. That means purging their voices and vocal mannerisms of distinctive traits. Unfortunately, it means they all sort of blur together as interchangeable A-List commodities. If you can’t get Ryan Reynolds and want to plug in Bradley Cooper you can do so without missing a beat. In an age when actors were distinctive, trading, say, Cary Grant out for Gary Cooper would mean making an entirely different picture.

So, this got me thinking about voices. Who were the great male voices of Hollywood, and what was it that made them great? I limited the inquiry to leading men, and my admittedly arbitrary criteria were as follows:

- Masculinity — A male voice is only aesthetically pleasing to the extent that it projects a masculine ethos. This requires a low register born of testosterone. This is a heavily weighted category.

- Emotiveness — The voice must retain its masculine ethos throughout the range of emotions the actor plays. That’s not to say pretty, because emotional turmoil can inflict dissonance, but the voice cannot strain weakly to meet the emotional requirements of the role.

- Distinctiveness — Another major criteria is that the voice must be unique and immediately recognizable.

- Range — The voice must move easily and naturally from the chest to the head without breaking.

So, without further ado, here are Hollywood’s All-Time Top 5 Male Speaking Voices.

Who are Hollywood’s All-Time Top 5 Male Speaking Voices?

5. Vincent Price — When Michael Jackson was creating Thriller, and needed a distinctive, campy, but menacing voice with gravitas, he turned to the Master of Gothic Horror. Famously overeducated, Price learned his acting craft on the job, on stage, where necessity proved the mother of his unique timbre. Having distinguished himself on Broadway, Price caught the discriminating ear of Orson Welles, and signed a five-show contract for The Mercury (Radio) Theatre. Though ultimately known for the horror films that made him wealthy, Price was not particularly fond of the genre, and was also adept at comedy and melodrama. One of my favorite Price performances has him taking a comic turn in the noir-ish romp His Kind of Woman with Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell, below.

4. Kirk Douglas —No throat could possibly vent the full force of charismatic rage Kirk Douglas carried inside him. Perhaps emanating from the depths of a tortured conscience, his voice always seems on the verge of a rupture. Sure, Kirk teeters on the brink of parody—if his jaw was set any tighter, he’d have been Jim Backus—but he always manages to make his anguish credible.

3. Humphrey Bogart — While most moviegoers might focus on Bogie’s famous lateral lisp, the rasp of his distinctive nasal baritone embodies the cynical detachment of many of his noir characters. Every line from Bogart’s mouth seems to be soaked in bourbon, cigarettes, and betrayal. Though Bogart could speak volumes through his eyes without uttering a word, his unique voice was the product of roughly 17 years on the stage before he began working steadily in film.

2. James Mason — If a speaking voice ever evoked the image of an iron fist in a velvet glove, it was Mason’s. Refined, seductive, and capable of quiet menace, Mason’s vocal instrument allowed him to play romantic leads and villains with equal panache. And, as his portrayal of the self-sabotaging alcoholic Norman Maine in A Star Is Born shows, Mason could project soul-shredding desperation without sounding unreasonably shrill. Below, his acidic pleasantness burns to the bone.

1. Gregory Peck — A perfect match of appearance and sound, Peck was at once ridiculously handsome and perhaps the most vocally virile leading man in Hollywood history. Rumbling like low thunder, Peck’s voice lent gravitas to his matinee idol looks, allowing him to play towering heroes, scowling outlaws and monomaniacal psychotics. And for those who might object that the previously cited actors are “too stagey” and their acting isn’t natural enough for contemporary tastes, Peck demonstrates we can have the best of both worlds. Trained by Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse, Peck mastered the leading technique for today’s film and TV naturalism.

Honorable mention: Cary Grant, Clark Gable, William Powell, Burt Lancaster, James Stewart, James Cagney, Charlton Heston, James Coburn, and Lee Marvin.

(My thanks to my friend, the talented photographer Barry Morgenstein for use of his photo of Rich Little.)

For your consideration:

Disclaimer: Links in this column may be affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link, the author receives a small commission on purchases for a limited time at no additional cost to you. These commissions help ensure future posts. Thank you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.