Humphrey Bogart struggles In a Lonely Place; terrorizes in The Desperate Hours

From The Petrified Forest to The Harder They Fall, Humphrey Bogart was the undisputed King of Film Noir. As Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, Bogey set the tone for hard-boiled gumshoes navigating “the great wrong place” and surviving the intrigues of the deadly femme fatale. In Key Largo, he embodied the soul-dead weariness of a disillusioned crusader, who’d concluded the world was just too rotten to save. Bogart was so noir, he could shed the shadows and fog, defying the disinfecting powers of sunlight, to play betrayal, corruption and revenge on the picturesque streets of San Francisco. In Dark Passage, with the help of a fortuitous self-defenestration, and after the necessary extermination of underworld vermin no one would miss, Bogart extricates himself from peril and achieves one of the rare happy endings in a film that is nevertheless truly noir.

That said, despite Humphrey Bogart’s curriculum vitae—or perhaps because of it—I have trouble accepting the following films as full-blooded noir. They’re missing too many elements I consider essential: the femme fatale, the underworld lurking beneath the respectable world, and the false step the hero takes to plunge himself into danger we know will ultimately be fatal. I know, I know, Dark Passage broke some rules, but it cleaved to others. In my admittedly subjective opinion, these films are not scrupulously noir; although noir—ish, they are more mainstream suspense thrillers. I welcome contrary opinions in the comment section below.

So, without further ado, let’s get started.

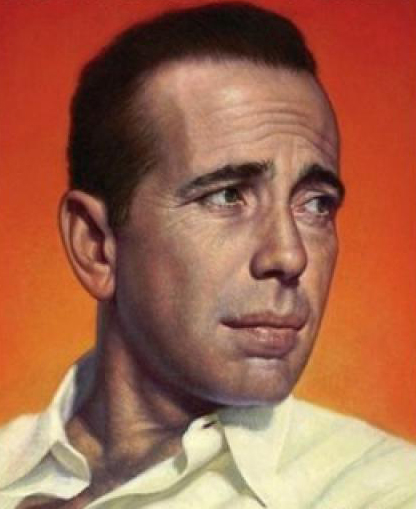

In a Lonely Place — Directed by Nicholas Ray, and loosely based on the 1947 novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, In a Lonely Place (1950) features the best performance of Gloria Grahame’s career and what many have called the most complex performance of Humphrey Bogart’s career. Ray first. A reliable and often interesting director, Ray is generally not recognized as a great director. His most famous film is Rebel Without a Cause, which for me grows more tedious with each viewing. Essentially The Breakfast Club with blood, Rebel tells a cloying tale of misunderstood/ mistreated teens who bond as outcasts, and is only elevated from obscurity by its talented cast, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo, who went on to better things before dying tragically (one a definite homicide, the other…eeeehhhhh), and James Dean, who achieved legendary status with fine acting, prematurely truncated by reckless driving.

Ray also directed a string of notable films, including They Live by Night (not They Drive by Night with Bogart), Knock on Any Door (with Bogart), The Flying Leathernecks (a serviceable John Wayne vehicle), The Lusty Men (not a porno, but an insightful look at rodeo performers with a great cast), The True Story of Jesse James (which no one really believes is true, but at least veers off the beaten Hollywood path of Robin Hood redux to depict James, played by Robert Wagner, as a murderous psychopath), 55 Days at Peking (in which 54 days are spent waiting for something to happen) and King of Kings (unfairly maligned as I Was a Teenage Jesus—Jeffrey Hunter was 36, older than Jesus himself). A solid career that deserves props if not effusive accolades. There may be underappreciated gems in Ray’s career that I haven’t yet discovered, but of the films I’ve seen, In a Lonely Place is the best.

Reclusive Dickson (Dix) Steele is a Hollywood, crime-film screenwriter, so absorbed in his work that he’s teetering on the brink between passionate romantic and psychotic strangler. When he’s linked to the victim of a late night murder, his new paramour, Grahame, is rightly unnerved. Complicating matters is Dix’s relationship with a homicide detective and his wife, who wonder if he might have slipped the rail.

Bogart, who practically owned the patent on cynical detachment, plumbs depths unimaginable from his prior roles. Scratch Rick Blaine, you’ll find a wounded narcissist; but you’d have to rent a backhoe to unearth Dix Steele (which, yes, I know is porno name to rival Dirk Diggler, but I’m trying not to go there). My point is that tough guy Bogey was more vulnerable as Dix than in any other role I’ve seen. And that’s not to say Bogart was an actor who relied on machismo or braggadocio. He often conceded the false facades of his characters to enrich the role. Remarkably enough, Louise Brooks, an actress who claimed to be an intimate of Bogart, said that Dix Steele came closest to the real Bogart she knew.

For her part, Gloria Grahame had a wide ranging and mostly underappreciated career playing supporting roles. Most moviegoers will recognize her as Violet Bix in It’s a Wonderful Life or Ado Annie in Oklahoma! An imperfect beauty, Grahame was relegated to secondary roles, but her skills shined in such noteworthy films as The Bad and the Beautiful (my favorite Kirk Douglas film) and Crossfire, an intense psychological drama centered around antisemitism. Grahame met Ray when she played in his second film, A Woman’s Secret. The two later married after an adulterous affair resulted in pregnancy. Thanks to Ray’s insistence that Grahame play the part of Laurel Grey, In a Lonely Place gave her the rare chance at a lead female. Judging by her superb handling of the nuances of her character, she should have had more. Grahame died young at age 57, a death sensitively portrayed by the lovely Annette Benning in a film worth viewing.

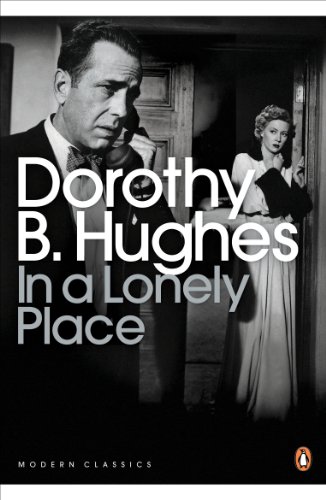

Yet the script from which Ray worked and the roles Bogart and Graham play are departures from the novel. In a Lonely Place was Hughes’ third book adapted to the screen. Her 1942 novel, The Fallen Sparrow was filmed in 1943, and her 1946 novel Ride the Pink Horse, also filmed with alacrity in 1947, produced a minor noir gem. Published in 1947, In a Lonely Place had too may sharp edges for classic Hollywood, thus, changes to the plot and characterizations were necessary.

In Hughes’ novel, Dix is not a waning screenwriter in need of a hit. He’s a poseur, much like Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s popular series of novels, but without being light in the loafers. It’s also clear from the very first pages that Dix is hiding a deep secret related to a series of stranglings in the West Hollywood area. Laurel, the Grahame role, is less important to this narrative, which consists mostly of Dix’s internal monologue as he concedes, denies, admits, retracts, and rationalizes thoughts related to the homicides his best friend Brub is investigating. Dix is the classic unreliable narrator, and the dramatic irony between what he admits and what we readers come to realize creates an unnerving air of suspense.

While the movie is certainly worth viewing, Hughes’ novel is a masterpiece in crime fiction. Hughes invites the reader into the disturbed psyche of her protagonist and proceeds to tease, titillate, disappoint, cajole, offend, frighten and evoke pity. I must admit that, early in, I wondered if I could keep reading, because the lonely place that Dix inhabited was bringing me to a dark place that I didn’t want to be in. My fertile imagination was filling in the gaps that Hughes had tastefully left empty. I’m glad I stuck with this book, although I now need to take a break from noir-ish reading for mental health reasons. My recommendation: dive in. A short stay In A Lonely Place is well worth the visit.

The Desperate Hours — Twenty-five-year-old writer Joseph Hayes won the Trifecta with this 1954 thriller. His first novel, it was a bestseller. The next year, he adapted it as a stage play which starred Paul Newman and Karl Malden, ran for 212 performances on Broadway, and won the 1955 Tony Award for Best Play. That same year, producer/director William Wyler had Hayes adapt that stage play as a film starring Humphrey Bogart and Frederick March. That’s a lot of mileage from a single idea, reportedly based on a real-life incident. But if that wasn’t enough, the movie was remade for TV in 1967 and got a theatrical reboot as Desperate Hours in 1990, this time starring Mickey Rourke and Anthony Hopkins.

The original film is a taut thriller about a suburban household invaded by three escaped convicts who hold a family hostage for a couple of days. The tension in the story relies heavily on the unlikely decision by the ringleader to keep up appearances by letting the head of the household and his 19-year-old daughter go about their business outside the home, while he keeps a gun poised over the wife and 10-year-old son. Wyler also goes a bit far out of his way to make the Liberal orthodox point that good people don’t settle their differences with guns. But for the most part, given the fine performances by the cast, led by Bogart and Frederick March, the film works as a suburban nightmare.

As for the book, I found it engrossing, with much more depth of character and many more moving parts than the film. The characterizations in the book are very different from the actors chosen for the film. Glenn Griffin, the ringleader, is described as young and tall, which is hardly the impression a viewer gets from the 54-year-old Bogart. (And though Paul Newman was young when he originated the role on Broadway, he’s also on the short side.) Jesse Webb, the Sheriff’s Deputy hunting the fugitives is described as young, tall and lean. One gets the impression of a young James Stewart, not the middle-aged Arthur Kennedy we get in the movie. But perhaps the greatest difference is the depth of character and consequential action taken by the daughter’s young boyfriend. Played in the film by Gig Young, he basically exists to be annoyed by the girl’s odd behavior. In the book, he’s a combat veteran who’s spurred to action.

The book suffers a bit by relying on characters making silly decisions to elevate the tension, but overall, it’s a fun escapist read that will surprise you here and there and draw you into the conflict, even if you’ve seen the film.

Disclaimer: Links in this column may be affiliate links. If you click on an affiliate link, the author receives a small commission on purchases for a limited time at no additional cost to you. These commissions help ensure future posts. Thank you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.